- Date posted

- Yesterday

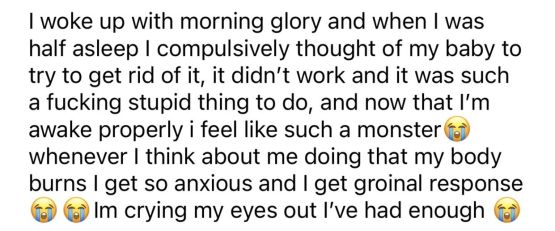

I've been stuck in a Real Event spiral for about a week now. It all has to do with my relationship and things that I've done/thought. I've been with my girlfriend for 10 years. I suspect I may have BPD (or a similar disorder), because for the first 4 or so years of our relationship, I exhibited a ton of really bad behavior and thought processes (partially due to very poor emotional regulation). I was controlling, unfaithful, impulsive, and always doing/thinking super fucked up things while thinking I was in the right. I had a huge victim complex. I spent years ruminating and confessing all of the events I could remember, along with some of the horrible ways I was thinking sometimes while engaging in these things. My girlfriend has been very hurt by me, but she has forgiven me and wants to continue our relationship due to my remorse, ability to take accountability, and changed behavior. I am horrified by the person I was between 16-20 (and a bit betond). I would do anything to go back on time and give myself a good beating. But I can't. When these episodes happen, it's all I think about from the moment I wake up until I go to bed. All I can do is research and ruminate and try to find out all of the details behind my fucked up intentions and mean thoughts. I try my best to just act normal around her and not give in to the extreme urge to confess, but it's killing me. I've spent years confessing, and all of the confessing really took a toll on my girlfriend. A lot of the things I've confessed were absolutely necessary, but she says that perhaps most things didn't need to be confessed. She prefers that I limit confessing as much as possible, and she doesn't really care to hear about things that center around my past thoughts. But what if those thoughts turned into some of the fuel for my terrible behaviors? Shouldn't she know then? What if the thought is tied into the action? What if the thought would make her not want to be with me anymore? That's my biggest fear. I've had thoughts that are so hurtful in the past that I'm afraid tjey would be the last straw for her. I'm so afraid of hurting her. I was such a monster, and she is the only person I give a damn about besides my direct family. I want to be with her forever. I would kill to marry her, but I feel like I can't as long as there are still these things that I haven't confessed. I don't even know if I have real event OCD considering I was such a deeply fucked up person. I know that I've confessed to her about hundreds of horrible things in the past. Why didn't I confess these things before she put a boundary on the confessing? What if these things are actually 100% vital for her to know, and I am conveniently abiding by her boundary to avoid ruining our relationship? Maybe this is something I should just tell her. I know it wouldn't help her, it would only make her sad, and it wasn't a specific action I did but something I thought about sometimes that may have made me justify those actions in my head. I was doing so good at not getting these confession urges for months. Now I feel like I'm dying. I don't want to hurt her and tell her this fucked up shit. It's not how I feel now. But she deserves to know the full extent of what a fuckup I was. I keep going back in my head, trying to figure out the ratio of bad thoughts and good thoughts I had about her. I feel like I'm mainly only remembering bad, hurtful things. I just wish I could have been a better person. I'm so afraid of losing the love of my life, the person that has stuck by me through my absolute lowest moments. She deserves so much better than me. I hate myself.

- Trigger warning

- Relationship OCD

- Real Events OCD

- LGBTQ+ with OCD